I was too young to lose money in the Dot-Com crash of 2000. I didn't own any tech stock. In fact, I didn't even know there was a bubble to pop. My interaction with the "Internet" was a dial-up modem sputtering to life and the simple, joyful ritual of visiting a handful of websites I had discovered.

When the NASDAQ plummeted and titans of vaporware like Pets.com vanished, nothing in my world seemed to change. The handful of websites I knew still worked. The internet still existed.

Yet we all became beneficiaries of that crash. We inherited fast and reliable internet infrastructure that would enable the likes of YouTube and Netflix. This didn't come out of nowhere. It was the enormous, tangible gift left behind by an era of spectacular overvaluation.

Fiber Optics and the Infrastructure Gold Rush

The Dot-Com era was built on a fantasy: growth at any cost. If you had a great domain name and a slide deck, that was all you needed to secure backing from a venture capitalist. Profit was someone else's problem, somewhere down the line. To support this vision of a trillion-dollar digital economy, billions were poured into physical infrastructure.

Telecom companies laid thousands of miles of fiber optic cables, convinced they would soon be transmitting massive amounts of data to every home and business. Warehouses filled with servers were erected to handle the unimaginable traffic that would surely materialize any day now. But the demand didn't materialize on their timetable. Most of the companies that financed this build-out collapsed, having over-delivered on infrastructure and under-delivered on sustainable business models.

As a result, the market was flooded with world-class infrastructure operating at a fraction of capacity. Companies like Global Crossing and WorldCom went bankrupt, leaving behind vast networks of "dark fibre". Cables that had been laid but never lit up with traffic. This excess capacity eventually drove down the cost of bandwidth dramatically, making fast, "always-on" broadband affordable and accessible for ordinary consumers. We, the users, inherited a massive, over-engineered highway system that failed companies had paid billions to build.

By the mid-2000s, this infrastructure became the foundation for an entirely new generation of internet services. YouTube launched in 2005, relying on cheap bandwidth to stream videos to millions. Netflix pivoted from DVDs to streaming in 2007, a business model that would have been economically impossible without the crash-induced glut of fiber capacity. The bubble's collapse didn't destroy the internet. It subsidized its golden age.

The Video Game Crash

In the early 1980s, the video game market was flooded with poorly made games and too many competing consoles. Store shelves were packed with rushed, derivative titles that diluted the market. The industry collapsed in 1983, with revenues plummeting by 97% and threatening to kill gaming as a commercial medium entirely.

Consumer trust wouldn't recover until 1985 with the release of the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). But Nintendo didn't just relaunch the industry. It fundamentally restructured it. The company introduced a "Seal of Quality" that enforced higher standards for games and established a new, more disciplined relationship between console makers and third-party developers. Nintendo limited how many games publishers could release per year, ensuring that only more polished titles reached consumers.

The crash didn't kill gaming; it served as a brutal, necessary editor that cleared away the junk and forced the industry to evolve. More importantly, Nintendo was at least partially responsible for bringing advanced computing into the living room as a mainstream product. As a result, it created the foundational experience that would shape how millions of people interacted with technology. The crash made room for excellence.

The Next Crash

Nvidia is investing $100 billion in OpenAI. OpenAI is committing $300 billion to Oracle. Oracle makes a $40 billion deal with Nvidia. Meanwhile, OpenAI is projected to generate just $13 billion in revenue in 2025. As kids say today, the math isn't mathing.

I believe we're in a bubble, though I'm not sure which stage we're at. Is this late 1999, with the peak still ahead? Or early 2000, with the foundation already cracking beneath us?

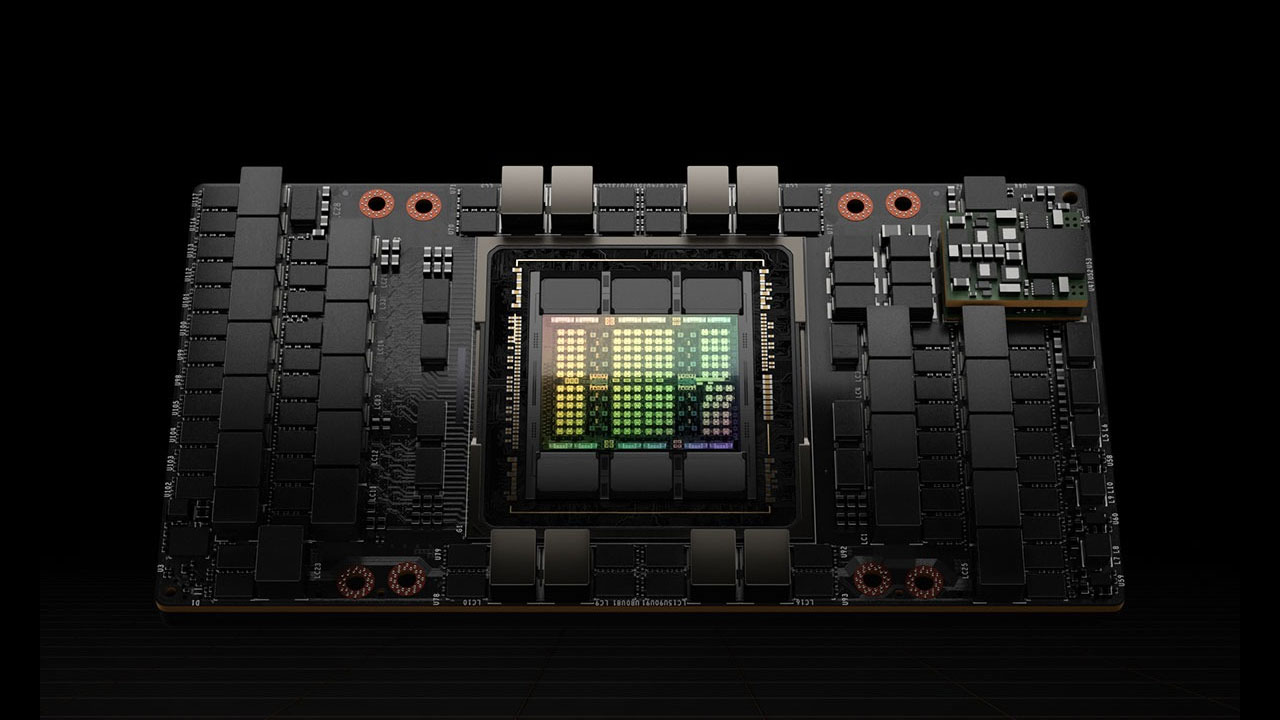

In the meantime, we're building. Specifically, we're building enormous quantities of High-Performance Computing (HPC) hardware, the GPUs needed to train and run large language models. The most sought-after is Nvidia's H100 GPU, a piece of silicon that costs tens of thousands of dollars and remains in short supply. Data centers are being constructed at breakneck speed, each one packed with thousands of these chips.

If the AI bubble pops. If hundreds of generative AI startups fail to find viable paths to profit before burning through their venture capital. We will once again be left with an enormous, tangible gift: graphic cards. Lots and lots of them.

Not free, perhaps, but certainly cheap. Millions of high-end GPUs currently locked away in underutilized data centers could flood the secondary market, creating a massive surplus of computing power available at a fraction of their original cost.

What Comes After

What would you do with a couple of H100s sitting on your desk? (first, get a bigger desk)

During the Dot-Com crash, I was too young to understand what was happening. But if the AI crash comes, and cheap hardware floods the market, it will enable a new generation of innovators to experiment without the gatekeeping of cloud providers and API rate limits.

I've written before about how AI is currently just a proxy for subscription companies, you rent access to models through monthly fees, with your data passing through corporate servers, etc. But when you and I can actually get the hardware in our hands, we can truly start to understand and reshape the power of AI on our own terms.

Imagine running the most powerful models entirely on local, specialized hardware, with complete privacy and unlimited customization. No data leaving your machine. No usage caps. No content filters imposed by nervous legal teams.

Imagine scientific research being conducted by individual researchers or small university labs, no longer priced out by cloud computing costs. A graduate student studying protein folding or climate modeling could have the same computational resources as a major corporation, all purchased secondhand for a fraction of the original price.

Imagine independent developers building entirely new applications we haven't conceived yet. Applications that would be economically impossible at current GPU prices but become viable when hardware costs collapse.

If the wheel of history repeats itself, we can expect decades of hardware advancement to land directly in the hands of the public. The infrastructure built for a bubble becomes the foundation for what comes next.

I, for one, am waiting for my free GPU. Or at least my heavily discounted one. The crash won't be the end of AI. It will be the moment AI becomes truly democratized.

Comments

There are no comments added yet.

Let's hear your thoughts