How fast is a horse? I was kinda baffled when I got the answer. For the average horse, one grazing in nature or on a ranch, they can go between 20 to 30 miles per hour. Doesn't that feel slow? What about race horses? I don't have a horse to clock it myself, so I'm relying on petmd.com. The website tells me that the English Thoroughbred can run for up to 44 miles per hour. It's fast alright. But I was going just as fast on my short commute to the office, and it didn't feel like I was racing at all.

Yes, cars have replaced horses. The animal has earned its retirement and now poses as a majestic novelty we feast on with our eyes. We don't use horses for transportation anymore. So, how fast is a car? More importantly, how much faster can a car go? And what does it take to increase the maximum speed?

I ask this question, because I believe there is a parallel with the growth trajectory of Large Language models. I've often heard people say: "This model you are using today is the worst version of an LLM you will ever use." This is to imply, it will only ever continue to improve. So let's go back to cars for a second.

When the first gasoline powered cars were manufactured in the late 1800s, the top speed was around 10 miles per hour. The Benz Motorwagen had a single cylinder engine capable of producing 0.75 horse power (hp). That's not even a full horse. I'm sure the general opinion at the time was that a car would never outperform a well bred horse. Yes, it was an impressive technology, but horses were not about to be replaced by this inefficient clunk of metal.

When OpenAI released their paper introducing GPT-1 in 2018, it didn't take the world by storm either. It was a good model with modest improvements over the existing natural language processors of the time. An improvement nevertheless, but we were not about to fire workers over the technology. This model was effective at some narrow task, but was worse than human-written text in general. But let's not forget that car performance didn't remain steady. They kept improving.

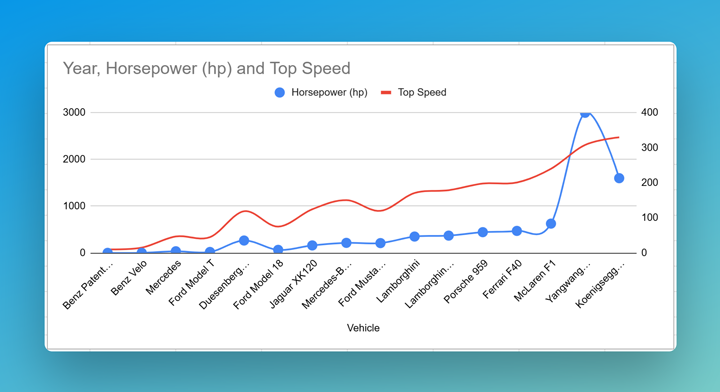

The successor to the Benz Motorwagen, the Benz Velo (1894), had a 3 hp engine and a top speed of 12 miles per hour. A small improvement. By 1901, the Mercedes had a 35 horse power engine and top speed of 47 mph. Not only was it faster than a horse, it could carry more than one horse ever could and for a longer distance. In 1927, an American company, Duesenberg, came up with the Model J that sported a massive 265 horsepower engine with 119 mph top speed. By 1967, we had the Lamborghini reaching 171 mph. In 1993, we had super cars like the McLaren F1 going 240 mph. We had unlocked the secret. More power = more speed.

150 years of Performance upgrade

GPT-3 was not just a transformer, it was transformative. Suddenly, "less is more" didn't make sense. Just like the car getting more horsepower improved the speed, the LLMs drastically benefitted from more data and more compute. ChatGPT, the product running GPT-3.5 initially, became mainstream. It wasn't reserved to research anymore, the general public had a field day with it. AI was everything. But just like the car, the promised exponential growth could only last for so long.

As of 2026, the fastest verified speed for a car came from the Yangwang U9 Xtreme with a recorded speed of 308.22 mph. Going from 240 mph to 308 mph required insane specialized engineering for miniscule real-world gain. The U9 has a 3000 HP engine. The car maker, Koenigsegg, "simulated" a theoretical max speed of 330 mph for their next car in production, the Jesko Absolut.

Large Language models are hitting that same wall. Scaling laws show diminishing returns. Adding 10x more compute might yield only a few percentage points on benchmarks. The "horsepower" (compute) is available in theory, but the "fuel" (quality data) is scarce and expensive.

And then there are speed limits. My car's 130 mph capability is irrelevant. Physics, safety and the law limit me to 65-90 mph. It is a great car for taking my kids to school, going on trips, or just my daily commute. Adding 1000 horsepower wouldn't improve my commute; it would just make any failure more catastrophic.

LLMs are approaching their utility speed limit. For most practical applications, GPT-4 level capability is 'fast enough'. They are great for writing an email, summarizing a document, and answering a customer's query. It's even great at helping me write code. But no amount of additional data will improve that courtesy email I wrote. The next breakthrough won't come from making it faster or more fluent. Instead, it will come from making it more reliable, truthful, efficient, and affordable. It's better brakes, airbags, and fuel economy. It's about obeying the speed limit of user trust.

In roughly 150 years, cars went from 10 miles per hour to 330 mph. And note that the unit of horsepower does not correlate to the power exerted by one horse. The horse in horsepower is honorary at best. Now, what if I told you that the car you are driving today is the slowest car you'll ever have to drive. Does it sound realistic? That's the argument we are making with large language models today.

We are giving a lot more horsepower with diminishing results. It would be irresponsible for me to ever drive at more than 90 mph on a perfect road, with perfect tires, in perfect weather. More horsepower won't get me to my driving destination any faster with increased risk.

Just as a car needs fuel and a bigger engine to go faster, the LLM recipe called for two ingredients: Data (Fuel) and Compute (Horsepower). We have run out of fuel. Companies have already scraped the available public human-generated data from the Internet. Books, blog text, news articles, video data, audio data. They have it all, including copyrighted and private data. What remains is either synthetic data, like content generated by AI models and fed back into training. The internet is increasingly polluted with LLM-generated text. It's like trying to power a car by siphoning its own exhaust."

And getting more horsepower is exponentially more expensive. Building a 3000-hp engine (a 100-trillion parameter model) is theoretically possible, but the energy cost is astronomical. OpenAI reported that they need increasing energy to power future models. They have partnered with other tech companies to build 20 Gigawatts of data center capacity. That's the equivalent of 20 nuclear power plants. Note that in the US, it takes 15 to 20 years to build a single nuclear power plant so that’s not even an option for their 2030 goal. They'll have to build 20 Nuclear power plants at the same time at an unprecedented speed to achieve their goal.

But even if this is achieved, we go back to the first problem: we don't have any more quality data. More power and bigger models, won't improve the quality of the output. When Yann LeCun says that LLMs are a dead end, this is what he means. Not that the technology doesn't work, but that we have already optimized the metrics, and more horsepower is not going to improve the models significantly. We are seeing this in effect when LLMs are becoming practically interchangeable. For most tasks, it doesn’t matter which model is winning in benchmarks, they will all summarize a document in an almost undiscernible manner.

If the problem with car speed was just more horse powers, we could theoretically attach a 10000 hp engine to a car. Just like we could theoretically cure all diseases, just kill it with fire. LLMs suffer the same problems, we can add more synthetic data, but that won't improve the model. We could provide more power, but that will just help us fail faster, at the cost of our non-renewable resources.

When we say "this is the worst version of an LLM you will ever use", we make the assumption that we are still in that exponential growth that new technology often benefits from. Going from 10 mph to 47 mph was game changing. But going from 120 mph to 170 mph hasn't improved our commute speed when the speed limit is 65 mph.

The quest for Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) has been the 'closed track' driving the obsession with raw scale. But unfettered speed is useless on public roads. The car didn't stop evolving when it maxed out its top speed. It evolved around it. It became safer, more efficient, more comfortable, and connected. The engineering shifted from pure power to practicality.

The race for sheer size is over. Now comes the real engineering: building models that reason reliably, verify their claims, and operate sustainably. Maybe even teach them how to say "I don't know." from time to time. We don't need faster cars. We need better transportation. We need models that operate in the real world.

Comments

There are no comments added yet.

Let's hear your thoughts