Programming insights to Storytelling, it's all here.

How do you manage a company with 50,000 employees? You need processes that give you visibility and control across every function such as technology, logistics, operations, and more. But the moment you try to create a single process to govern everyone, it stops working for anyone.

Let's do this thought experiment together. I have a little box. I'll place the box on the table. Now I'll open the little box and put all the arguments against large language models in it. I'll put all the arguments, including my own. Now, I'll close the box and leave it on the table.

Sometimes, I have 50 tabs open. Looking for a single piece of information ends up being a rapid click on each tab until I find what I'm looking for. Somehow, every time I get to that LinkedIn tab, I pause for a second. I just have to click on the little red dot in the top right corner, see that there is nothing new, then resume my clicking. Why is that? Why can't I ignore the red notification badge?

A few years back, the term "AI" took an unexpected turn when it was redefined as "Actual Indian". As in, a person in India operating the machine remotely.

How did we do it before ChatGPT? How did we write full sentences, connect ideas into a coherent arc, solve problems that had no obvious answer? We thought. That's it. We simply sat with discomfort long enough for something to emerge.

A college student on his spring break contacted me for a meeting. At the time, I had my own startup and was navigating the world of startup school with Y Combinator and the publicity from TechCrunch. This student wanted to meet with me to gain insight on the project he was working on. We met in a cafe, and he went straight to business. He opened his MacBook Pro, and I glimpsed at the website he and his partner had created.

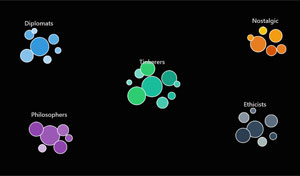

Whenever one of my articles reaches some popularity, I tend not to participate in the discussion. A few weeks back, I told a story about me, my neighbor and an UHF remote. The story took on a life of its own on Hackernews before I could answer any questions. But reading through the comment section, I noticed a pattern on how comments form. People were not necessarily talking about my article. They had turned into factions.

Last year, all my non-programmer friends were building apps. Yet today, those apps are nowhere to be found. Everyone followed the ads. They signed up for Lovable and all the fancy app-building services that exist. My LinkedIn feed was filled with PMs who had discovered new powers. Some posted bullet-point lists of "things to do to be successful with AI." "Don't work hard, work smart," they said, as if it were a deep insight.

My favorite piece of technology in science fiction isn't lightsabers, flying spaceships, or even robots. It's AI. But not just any AI. My favorite is the one in the TV show The Expanse. If you watch The Expanse, the most advanced technology is, of course, the Epstein drive (an unfortunate name in this day and age). In their universe, humanity can travel to distant planets, the Belt, and Mars. Mars has the most high-tech military, which is incredibly cool. But the AI is still what impresses me most. If you watched the show, you're probably wondering what the hell I'm talking about right now. Because there is no mention of AI ever. The AI is barely visible. In fact, it's not visible at all. Most of the time, there aren't even voices. Instead, their computer interfaces respond directly to voice and gesture commands without returning any sass.

At an old job, we used WordPress for the companion blog for our web services. This website was getting hacked every couple of weeks. We had a process in place to open all the WordPress pages, generate the cache, then remove write permissions on the files.