Programming insights to Storytelling, it's all here.

That's the answer I would always get from the lead developer on my team, many years ago. I wanted clear, concise answers from someone with experience, yet he never said "Yes" or "No." It was always "It depends."

I have a hard time listening to music while working. I know a lot of people do it, but whenever I need to focus on a problem, I have to hunt down the tab playing music and pause it. And yet I still wear my headphones. Not to listen to anything, but to signal to whoever is approaching my desk that I am working. It doesn't deter everyone, but it buys me the time I need to stay focused a little longer.

Last year, I pushed myself to write and publish every other day for the whole year. I had accumulated a large number of subjects over the years, and I was ready to start blogging again. After writing a dozen or so articles, I couldn't keep up. What was I thinking? 180 articles in a year is too much. I barely wrote 4 articles in 2024. But there was this new emerging technology that people wouldn't stop talking about. What if I used it to help me achieve my goal?

How do you manage a company with 50,000 employees? You need processes that give you visibility and control across every function such as technology, logistics, operations, and more. But the moment you try to create a single process to govern everyone, it stops working for anyone.

Let's do this thought experiment together. I have a little box. I'll place the box on the table. Now I'll open the little box and put all the arguments against large language models in it. I'll put all the arguments, including my own. Now, I'll close the box and leave it on the table.

Sometimes, I have 50 tabs open. Looking for a single piece of information ends up being a rapid click on each tab until I find what I'm looking for. Somehow, every time I get to that LinkedIn tab, I pause for a second. I just have to click on the little red dot in the top right corner, see that there is nothing new, then resume my clicking. Why is that? Why can't I ignore the red notification badge?

A few years back, the term "AI" took an unexpected turn when it was redefined as "Actual Indian". As in, a person in India operating the machine remotely.

How did we do it before ChatGPT? How did we write full sentences, connect ideas into a coherent arc, solve problems that had no obvious answer? We thought. That's it. We simply sat with discomfort long enough for something to emerge.

A college student on his spring break contacted me for a meeting. At the time, I had my own startup and was navigating the world of startup school with Y Combinator and the publicity from TechCrunch. This student wanted to meet with me to gain insight on the project he was working on. We met in a cafe, and he went straight to business. He opened his MacBook Pro, and I glimpsed at the website he and his partner had created.

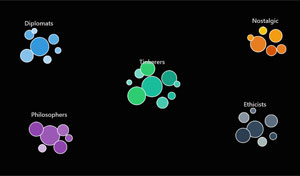

Whenever one of my articles reaches some popularity, I tend not to participate in the discussion. A few weeks back, I told a story about me, my neighbor and an UHF remote. The story took on a life of its own on Hackernews before I could answer any questions. But reading through the comment section, I noticed a pattern on how comments form. People were not necessarily talking about my article. They had turned into factions.